Taking the Moose Lodge to Court

K. Leroy Irvis and the Legal Battle against Segregation in Harrisburg

Five years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, an act that outlawed racial segregation and discrimination across the country, an African American legislator was denied service at a restaurant on the banks of the Susquehanna. This story, an all too common one in the 20th century, is the story of K. Leroy Irvis, a native Pittsburgher, once a member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, and now, a man remembered as a key figure in our state’s civil rights history.

On 225 State Street in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, less than 500 feet from the Capitol building, the Moose Lodge no. 107 sat as the local branch of an international organization called The Loyal Order of Moose. Founded in Louisville, Kentucky in 1888, the purpose of this fraternal order was “to serve a modest goal of offering men an opportunity to gather socially, to care for one another’s needs and celebrate life together.” The Order was headquartered in Mooseheart, Illinois, a strictly segregated unincorporated community. The discriminatory practices of the headquarters passed down to all the Lodges that fell under their jurisdiction.

Traveling for a late dinner with fellow Democrat and Pennsylvania Speaker of the House-designate Herbert Fineman, as well as another unidentified gentleman, House Majority Leader K. Leroy Irvis and his group decided to scout out Harrisburg’s local branch of the Moose Lodge as a potential venue for a larger dinner later in the year. One of their trio was already a Moose himself, and per the club’s rules, two guests were permitted to follow him in for a visit. However, upon arriving, Mr. Irvis and his retinue were denied dinner menus, being told “there was no food in the place,” despite seeing numerous white patrons dining all around them, according to The Pittsburgh Press. No stranger to prior experiences of segregation, Irvis told the Press this wasn’t the first time he’d been denied service on account of his race, but he added that he later realized, “it was more important to my people than just to myself that we be treated fairly. I have decided I will do something about this.”

Three years later in 1972, Irvis brought the issue through the courts. In City Contented, City Discontented, Harrisburg journalist Paul Beers recounted Irvis’ tale: “before he was finished, Attorney Irvis had the Moose before the U.S. Supreme Court.” In Moose Lodge no. 107 v. Irvis, he leaned on the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which states that no state may “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Irvis argued that since the Moose Lodge’s State-granted right to a liquor license made the Lodge a State-governed entity, it was subject to the Equal Protection Clause and thus could no longer maintain racially discriminatory bylaws. The District Court agreed with Irvis’ motion, but his opponent took the issue to the highest court in the land.

The Supreme Court utilized a 1961 case from Delaware to compare with Irvis’ claim: Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority. In that case, a failed sit-in by seven African American workers at the Eagle Coffee Shoppe led to an immense legal dispute, in which a city councilman, William H. Burton, leaned on the Equal Protection Clause to attack the business for refusing him service. In that case, the Eagle Coffee Shoppe was found to be closely intertwined with the city’s Parking Authority, who was financing the parking space outside its walls, and was in this way a “state actor” and subject to the consequences of the Equal Protection Clause.

The Moose Lodge had no such connection with any State-operated groups, however, and though their practices were discriminatory in nature, they remained private and untouchable by the legal power of the Clause. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Lodge, and Irvis lost the case. Nevertheless, Irvis’ case against the Moose would have a lasting impact. His efforts in fact marked the beginning of the end for racial discrimination in private clubs across the nation. Just one year later in Brunswick, Maine, the Elks Lodge had its liquor license revoked for racial discrimination by the state Supreme Judicial Court on December 11, 1972.

In time, even after clubs like the Moose or the Elks Lodge opened their membership to non-whites, membership within these groups began to fall. In 1994, the Order came under fire once again after a Maryland branch of the Lodge in Hagerstown denied membership to an African American car dealership worker solely on account of his race. Just over one week later, the governing Moose International would revoke the Lodge’s charter and close the location permanently, displacing eight thousand members – a loss of the Order’s largest branch in the world.

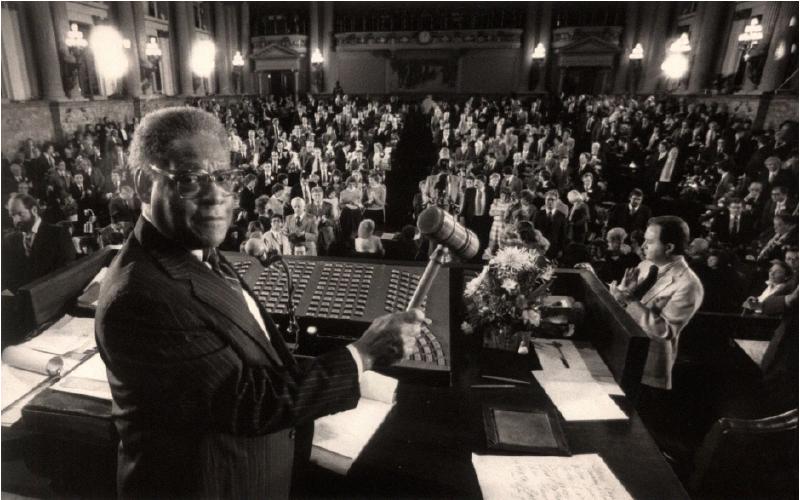

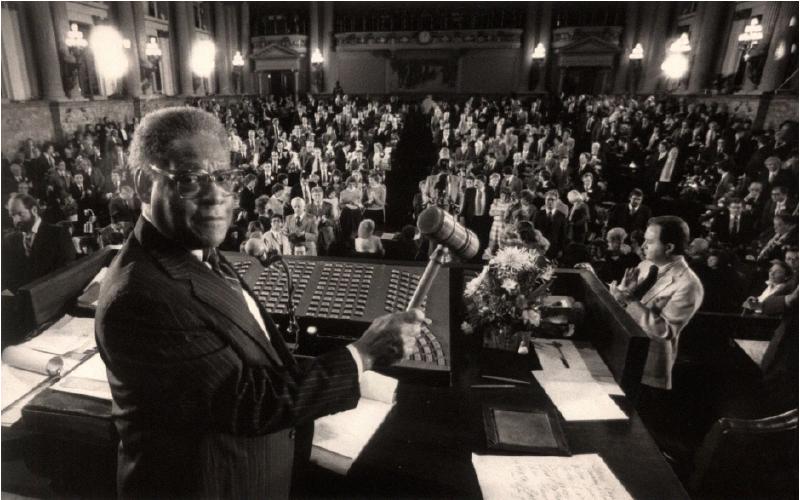

The changing social pressures of passing generations eventually did what the law could not – and economic discrimination in all organized forms was eradicated across the nation. Years later, Irvis continued to serve as a statesman, notching two terms as Speaker of the House in 1977 and 1983 in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.

Today, Irvis is honored as a speaker, a leader, and a Pennsylvania native who stood up to discrimination within the borders of his home state, and his story was the catalyst for a wave of social changes across the nation. In Harrisburg, The Commonwealth Monument Project has sought to honor Irvis’ name by christening the grounds on which “A Gathering at the Crossroads” monument stands as the K. Leroy Irvis Equality Circle, a testament to the life and legacy of a voice for equality, unity, and progress in the name of justice for all.

A full list of the resources used in this story can be accessed here.

Related Stories

A Gathering at the Crossroads

Green Book Harrisburg

Images