Harrisburg's Role in the Underground Railroad

The Heart of the Central Route

Harrisburg, PA connected southern states and western cities to larger hubs along the Underground Route railroad, making it the heart of the central route. Anti-slavery committees, abolitionists, and advocacy groups created pathways, safehouses, and resources for freedom seekers to travel northward towards independence.

When people hear the phrase “The Underground Railroad,” they often imagine Harriet Tubman leading groups of terrified freedom seekers through the countryside in the middle of the night. They hear gunshots, barking dogs, and shouts characterized by a southern twang echoing in the distance. Many do not imagine the city of Harrisburg playing a crucial role in the Underground Railroad.

Yet, Harrisburg represented the heart of the Central Route of the Northern Underground Railroad system due to its large Black population and long history as the capital city of a free state. Escape routes lead to and from the city creating four major exit routes for freedom seekers to travel.

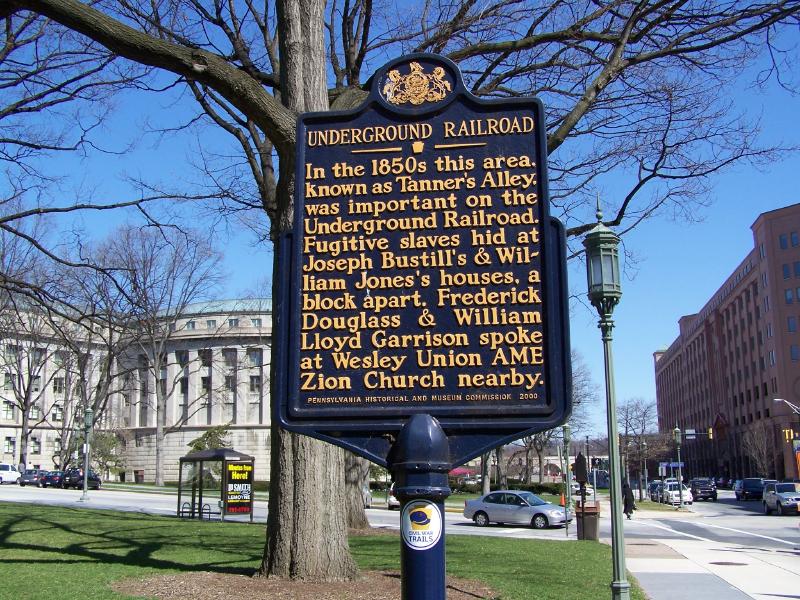

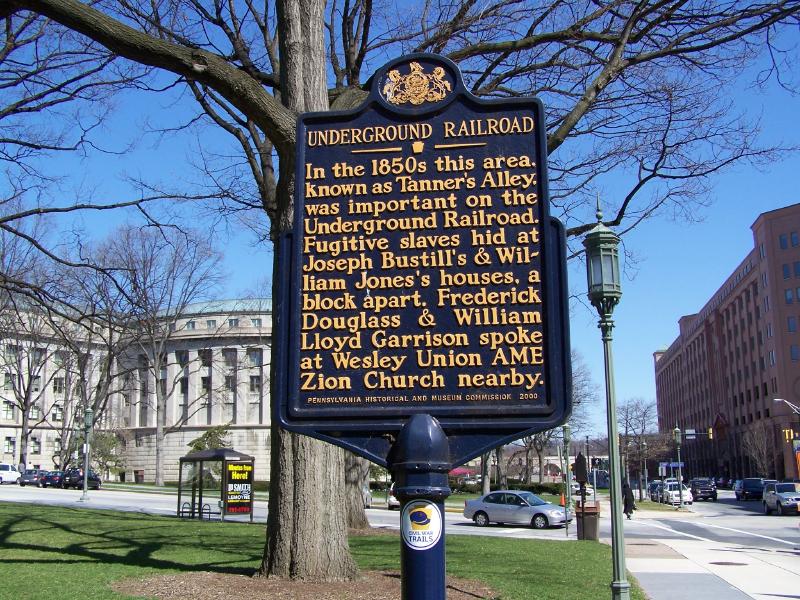

A Pennsylvania state marker, located on Walnut Street near the Commonwealth Monument in the Pennsylvania State Capitol Complex, briefly describes Harrisburg’s participation in the Underground Railroad. It identifies the roles of Wesley Union AME Church, Joseph Bustill, and William Jones in hiding and assisting freedom seekers. In the 1850s, the area connecting these individuals and institutions was known as Tanner’s Alley and numbered among the city’s most important Black neighborhoods. It is now recognized as a prominent location in Harrisburg’s Underground Railroad.

Wesley Union Church, the first Black church in Harrisburg, was founded in 1829. In 1836, the Harrisburg Fugitive Slavery Society, an informal society that sent freedom seekers to Philadelphia, began using the church and its reach among the Black community to promote abolition. Historical sources provide the names of a number of Harrisburgers involved in the Underground Railroad.

One of these was Joseph Cassey Bustill, an African American schoolteacher born in Philadelphia to a distinguished family. Joseph joined the Underground Railroad at seventeen and was perhaps the youngest member of the movement. According to Bustill’s daughter, Bustill made use of homes, churches, halls and lodging rooms to help the fugitives. Furthermore, Bustill assisted in the formation of the Harrisburg Fugitive Slave Society, and often contacted William Still regarding the arrival of freedom seekers in Philadelphia, referring to them as “packages” nearing “delivery.”

Another was William “Pap” Jones, an African American doctor whose home served as the site of his medical practice and a refuge for freedom seekers. The Jones residence was one of the primary stations on the Underground Railroad in Harrisburg, where Dr. Jones and his wife, Mary, provided a safe space to rest and ample provisions for the journey ahead. Dr. Jones transported freedom seekers to their next station on the Underground Railroad via a covered wagon operating under the guise of a “rag merchant.” Through his extensive knowledge of the routes leading North and collaboration with fellow guides, Dr. Jones brought many freedom seekers closer to safety.

Harriet McClintock Marshall, born in Harrisburg in 1840, was also a conductor on the Harrisburg Underground Railroad, likely working through the Wesley Union AME Church founded by her mother. Harriet and her husband Elisha Marshall, a former freedom seeker, opened their home as a safe house and offered refuge, food, and clothing to those seeking freedom.

Harrisburg also connected freedom seekers to the Vigilant Committee of Philadelphia. The Vigilant Committee was formed by Robert Purvis in 1837 to “create a fund to aid [Black Americans] in distress.” The committee appointed officers, raised money, and made resources available to assist freedom seekers attempting to live in or pass through Philadelphia on their way further north. Although the original committee was disbanded in 1852, another quickly took its place with Purvis as the head of the general committee.

The Vigilant Committee was responsible for the aid of a great number of freedom seekers and their families. As one example of how the network functioned, we can look at the travels of the Taylor family, a notable family aided by these committee resources.

In 1856, Owen and Mary Ann Taylor and family fled Clear Spring, Maryland in a desperate attempt to claim freedom. Owen Taylor and his brothers had been enslaved by farmer Henry Fiery and one of his sons. The Taylor brothers harnessed horses belonging to Fiery, placed their families in the carriage, and began their journey north. The eight freedom seekers traveled eighty-seven miles from Clear Spring to Harrisburg, crossing the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, and traveling through Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. From there, the group made their way to Philadelphia, where they were met by the Vigilant Committee.

Henry Fiery quickly realized the Taylors were missing and began communication with Joseph C. Bustill, who assured Fiery he’d work to return the group. However, correspondence between Bustill and other Underground Railroad conductors reveals just the opposite. Bustill, despite being in contact with enslavers, actively worked against them and aided freedom seekers, directing them to safe spaces farther north. The remarkable story of Owen Taylor and his family accounts for only a single narrative within the broad scope of Harrisburg’s rich history regarding the Underground Railroad.

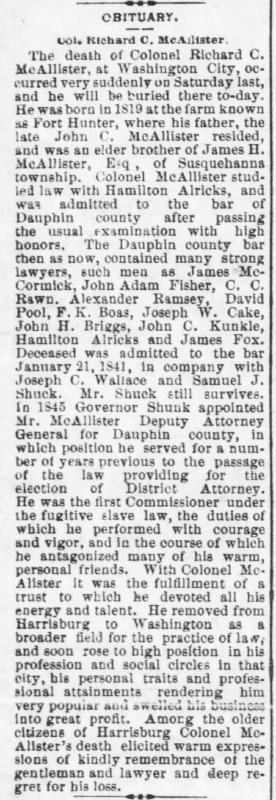

Despite Harrisburg’s historic presence of Black freedmen, the anti-slavery fight faced adversity during the 1850s. The Fugitive Slave Act (1850) required enslaved people to be returned to their enslavers even if they were in a free state. The same year, a Slave Commission office opened in Harrisburg. Richard McAllister, local attorney and commissioner, was infamous for seizing Blacks, fugitives or free, and sending them to the slave market to be resold. McAllister had a notorious reputation. As the historian, R. J. M. Blackett noted, McAllister boasted that “more fugitives have been remanded by me than any other U.S. Com.” He asserted the Fugitive Slave Law should be kept harshly to protect the “peace and interest of the country.” By 1852, the congregation of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Harrisburg gave McAllister an ultimatum: he could resign as commissioner or forfeit his position as Vestryman. McAllister chose the former and resigned as slave commissioner in 1852. By 1853, the Slave Commission office ceased operations. After McAllister resigned, Harrisburg more freely aided countless freedom seekers in their journey north.

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania played a critical role for those seeking freedom for themselves and their families. There are many more stories of Harrisburg area residents who helped aid freedom seekers, including Henry Watson, Daniel Kaufmen, Jacob Shockley, Hiram E. Werz, James McCallister, Dr. William W. Rutherford of Front Street, and Reverend James Graham. Indeed, Harrisburg and its residents helped innumerable freedom seekers to safety. Their lives and the history of the city are forever intertwined in the fight against slavery, a time that represents a pivotal period in American history.

A full list of the resources used in this story can be found here.

Related Stories

Men of God

Images