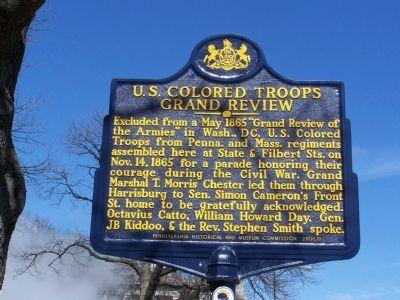

Welcome Home USCT

Harrisburg’s Grand Review for Black Veterans of the Civil War

When Civil War soldiers were recognized in a Grand Review march in Washington, DC, the United States Colored Troops (USCT) were excluded. The city of Harrisburg, PA held its own Grand Review March on May 23-24, 1865 to recognize the struggle and participation of the Black soldiers in their fight for freedom.

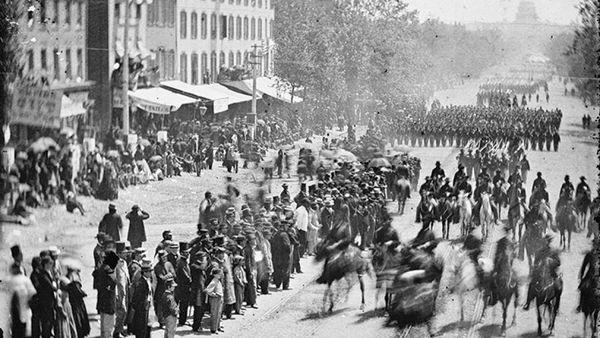

On the morning of November 14th1865, the streets of Harrisburg echoed with the footsteps of regiments from the United States Colored Troops (USCT) bearing arms. Beginning at 10:00am, the soldiers marched from Filbert and State Street (now Soldier’s Grove), through the Eighth Ward, up Market Street, and along Front Street past Simon Cameron’s home. Cameron, Lincoln’s former Secretary of War, watched approvingly from his porch. His remarks, reprinted in the North American and United States Gazette in Philadelphia on November 15, 1865, honored the troops: “I cannot let this opportunity pass without thanking the African soldiers…for the great service which they have been to their country in the terrible rebellion.”

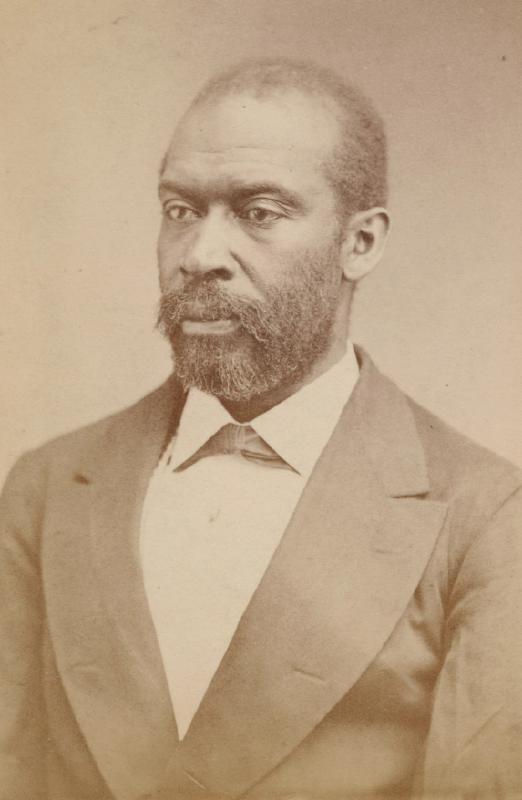

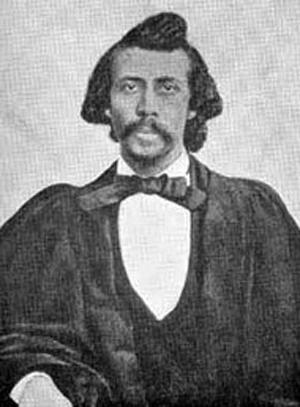

These soldiers marched in the Harrisburg Grand Review, a historic event planned to honor the thousands of Black soldiers who fought in the United States Civil War for the Union Army. The Garnett League, Harrisburg’s chapter of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League, determined that the USCT deserved recognition for their contributions to the Northern victory and, alongside Harrisburg community members and political figures, organized the Grand Review. Thomas Morris Chester, who served as both Chief Marshall and Chairman of the Committee of Arrangements, led the march. A Harrisburg native himself, Chester served in the USCT and was the United States’ first Black war correspondent.

On the steps of the Capitol Building, William Howard Day, Orator of the Review, delivered a long address, and a letter from Generals Meade and Butler was read to the attendees after the procession through Harrisburg. Thousands of Harrisburg citizens, white and Black, lined the streets, showing their support and gratitude to the men who fought for their own freedom in the United States Civil War.

The controversial decision to permit Black Americans into the United States Army was made in the midst of the Civil War. Toward the beginning of the conflict, the Northern armies still followed the Militia Act of 1792, allowing only white male citizens to participate in militias. The Northern armies attempted to abide by this act, but midway through the war, states struggled to meet their volunteer quotas and sought a new way to recruit soldiers. Then came the Militia Act of 1862. Enacted on July 17, 1862, the new act authorized a state militia draft when volunteer quotas were not met, and for the first time, allowed African Americans to serve in militias as soldiers or laborers. Abolitionists in the North praised this controversial decision as a step toward equality.

Many Black residents of Harrisburg served in the Civil War through the USCT. One such man was Henry C. Keith, who enlisted in September of 1863. Keith enlisted in the 8th USCT Company B, which underwent rigorous training at Camp William Penn near Philadelphia before deployment to the Easter Theater. Company B fought in significant combat, particularly during the Battle of Olustee on February 20, 1864, which ended in a Confederate victory. Keith survived the intense combat that characterized the Civil War and eventually started a family and became a policeman in 1885.

Ephraim Slaughter was another USCT soldier with ties to Harrisburg. In 1863, he escaped slavery in North Carolina and joined Company B of the 3rd North Carolina Colored Infantry (Later the 37th USCT) in January of 1864. After the war, Slaughter settled in Harrisburg’s Old Eighth Ward, where he was a real estate investor and active member of Bethel AME Church. When he died in 1943, Slaughter was Harrisburg’s last surviving Civil War veteran.

Roughly 179,000 Black men served as soldiers in the United States Army, 19,000 more having served in the United States Navy. By the end of the Civil War, almost 40,000 Black soldiers died, 30,000 as a result of infection or disease. They served in artillery and infantry while performing all the non-combat functions that support and sustain the armies as well. According to the National Archives, Black carpenters, guards, laborers, nurses, spies, scouts, surgeons, etc. contributed to the war. There were almost eighty Black commissioned officers. Confederate troops often targeted Black soldiers, who faced crueler conditions if captured. Black Americans proceeded to enlist anyway, a testament to their bravery and sacrifice.

After four years of intense fighting and high casualty numbers, the Confederacy surrendered. A month later, on May 23-24, 1865, the Northern Armies completed their final military march, the Grand Review, which moved from the US Capitol toward the White House. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, was quoted, “You see in these armies, the foundation of the Republic: our future railroad managers, congressmen, bank presidents, manufacturers, judges, governors, and diplomats; yes and not less than a half dozen presidents.”

But not a single Black American who’d bravely fought in the Civil War was represented in May’s Grand Review in Washington D.C.

The Militia Act of 1862 was perhaps the governmental change that enabled the Union to defeat the Confederacy in a war fought primarily over the future of Black Americans. Even so, the members of the USCT were intentionally excluded from the Grand Review March in Washington D.C. In response, Harrisburg organized its own Review. This distinctive move towards equality was supported by formal committees and citizens alike, with a great number of citizens, white and Black, coming to pay respect to the soldiers of the USCT and their role in the Union Army victory.

According to the November 15, 1865 edition of the North American and United States Gazette, “The reception of these troops was, as it should be, respectful and honorable by the mass of the people of Harrisburg, and many a fair white hand did not shrink from waving a kerchief in welcome of those who escaped the perils of a contest in which they risked their lives, in defense of the national honor and support of the constitutional authorities.”

Orator William Howard Day believed the Union victory in the American Civil War represented a future of “improvement, social elevation, and the acquirement of political rights.”

One hundred and thirty four Black Civil War veterans, including Chester, Keith, and Slaughter, are buried at Harrisburg’s Lincoln Cemetery. The city’s oldest surviving African American burial ground, Lincoln Cemetery was established in January 1876. In the words of Rachael Williams, Executive Director of SOAL, an organization working to restore and preserve Lincoln Cemetery, it “stands as a symbol of resilience and unity within the community.” Other notable Black veterans buried there include Aquila H. Amos, James M. Auter, and Harry F. Flowers. Their memories–and the memories of the thousands of other Black Americans who served in the USCT–are honored through the retelling of their stories and the significant role they played in the fight for freedom and equality during the American Civil War.

A full list of the resources used in this story can be found here.

Related Stories

Men of Muscle

It's a Family Business

Lincoln's Close Call

Images